Research

Research Summary

The effectiveness of SIS has been tested using behavioral and self-report measures with follow-up periods as long as 19 months after training

- After SIS, youth are about 4 times less likely to have substance abuse related school suspensions.

- High school students who receive SIS training are 4.5 times less likely to have juvenile criminal police offenses such as assaults, vandalism, burglary, runaway, etc., compared to youth who did not have SIS training for 19 months after training. Juvenile criminal police offenses were not found to be different for the two groups for six months prior to the SIS training for the treatment group.

- After SIS, precocious sexual behavior, pregnancy, and fights that lead to violence are reported to cease.

- Statistically significant increases in behavioral intentions to implement constructive decisions in difficult situations have been found in all age groups in schools, juvenile detention and probation, group homes, alternative schools for pregnant teens and teens with other problem behaviors and in chemical dependency treatment.

- After SIS, adults and youth, have statistically significant increases in quality of life and empowering communications/behavior that count oneself, others and issues, and reductions in disempowering communications such as people-pleasing, blaming, bullying, being sarcastic, threatening, carrying grudges, lecturing or playing smart, disrupting, “spacing out” or being irrelevant.

- After SIS in residential chemical dependency treatment with adults SIS leads to significant decreases in disempowering communications/behaviors, alienation/normlessness and leaving treatment against medical advice,

Research Results

One of three middle schools (grades 6-8) in a city of about 80,000 was randomly assigned to receive Say It Straight Training (SIS) and two schools were assigned the role of control school. The two control schools received their own information-oriented drug-prevention program. The school receiving SIS was compared with the two control schools on alcohol/drug related school suspensions and referrals during the whole academic year. A total of 509 students participated in SIS. Of these, 202 were sixth graders, 215 were seventh graders, and 92 were eighth graders. In the two control schools, 1,539 students were measured on alcohol and drug-related school suspensions and referrals. In addition, the Say It Straight Social Skills Questionnaire was administered to students in the school that received SIS and a small subset of students in one of the control schools before and after their respective trainings. The SIS Social Skills Questionnaire measures student willingness to implement constructive decisions in difficult situations and how they feel doing so (an increase in the SIS Social Skills Questionnaire indicates a greater willingness to implement constructive decisions in difficult situations and feel more at ease doing so). A Subjective Feedback Questionnaire was administered in the school that received SIS after the training. This questionnaire gives students the opportunity to write in their own words what they learned and what was useful to them in the training. On the Subjective Feedback Questionnaire students indicated that they had learned and were motivated to use the skills and knowledge taught by the program when faced with a relevant situation in real life.

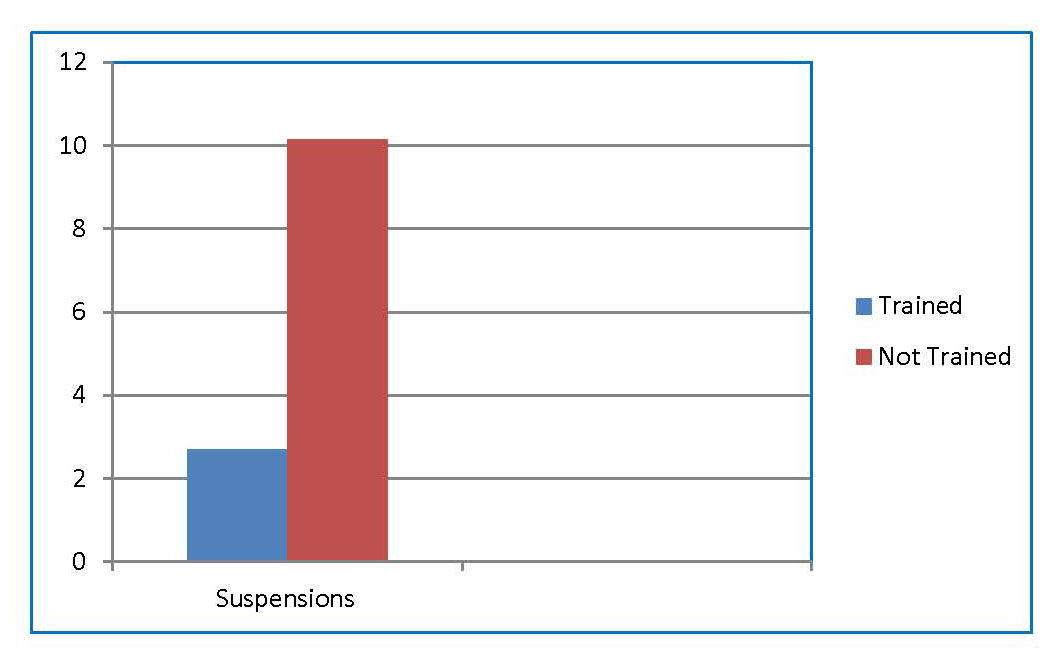

Students in the school that received SIS were 2.4 times less likely to have alcohol and other drug related school suspensions and referrals during the academic year compared to students in the two control schools. This is a highly statistically significant result. It is interesting to note that of the 12 suspensions and referrals that occurred in the school that received SIS, not a single one occurred after SIS. Students trained in the school that received SIS were followed during the next whole academic year. Not a single “new user” (defined by alcohol and other drug related school suspensions) was identified among them. In addition, only students in the school that received SIS showed statistically significant positive shifts on the SIS Social Skills Questionnaire that indicated a greater willingness to implement constructive decisions in difficult situations and feel more at ease doing so after SIS. These shifts were highly statistically significant.

Because of the success of SIS in the treatment school in Study 1, SIS was requested in one of the previous year’s control schools. Furthermore, the original treatment school asked Dr. Englander-Golden to do SIS with all the incoming 6th graders and do SIS reinforcement with 7th and 8th graders who had been trained as 6th and 7th graders the year before. Finally, one elementary school asked that their 5th graders also be offered SIS. Alcohol/drug related school suspensions were monitored for all 5th-9th grade students in the city during the whole academic year. This included the 9th graders trained as 8th graders in Study #1. The SIS Social Skills Questionnaire was administered before and after training to the 5th graders, the incoming 6th graders in the school that received SIS in the previous year and to 6th-8th graders in one of the previous year’s control schools. The Subjective Feedback Questionnaire was administered after SIS.

Alcohol/drug related school suspensions were significantly lower among the 1483 6th – 9th graders who received SIS compared to 1295 students who did not have SIS. Trained students were 3.7 times less likely to have an alcohol/drug related school suspension compared to untrained students during the academic year. The 5th graders were excluded from this analysis because no such suspensions were incurred either by trained or not trained 5th graders. Scores on the SIS Social Skills Questionnaire showed highly statistically significant increases for 5th-8th graders after SIS. A subjective feedback questionnaire was also administered to these students. As in Study #1, in every grade students reported on the Subjective Feedback Questionnaire that they had learned and were motivated to use the skills learned.

The graph below shows significantly lower alcohol/drug related school suspensions per 1,000 students during the 1983-84 school year among 1,483 trained and 1,295 untrained 6th-9th graders in a town with a population of about 80,000 (Chi Square = 4.98, df = 1, p < 0.03). There were four suspensions among the trained students and 13 among the untrained students. About 30% of the trained students were trained during the previous school year. Thus, we are seeing long term effects of SIS training.

ALCOHOL/DRUG RELATED SCHOOL SUSPENSIONS

Among Trained and Untrained 6th-9th Graders Per 1,000 Students

DOWNLOAD COMMUNICATION SKILLS AND SELF-ESTEEM IN PREVENTION OF DESTRUCTIVE BEHAVIORS

This study demonstrates the long-range effectiveness of SIS in reducing the number of juvenile police offenders among 9th-12th graders. A six month pre-training base line period was used to monitor juvenile police offenders among all 740 9th-12th graders in a city with a population of about 5,000. The most rigorous design was applied to the 9th grade. SIS was offered to all 9th graders and 186 out of 208 participated. The number of juvenile offenders among this trained group of students was compared to offenders among 211 9th graders who were not trained during the following school year and thus provided a control group. Comparisons for these two groups were done during equivalent time frames (February 1 through August 24) of two consecutive years. SIS was also conducted with 108 out of 221 10th graders, 35 out of 166 11th graders and 28 out of 145 12 graders. In addition to measuring juvenile police offenses, participants in the program were administered the SIS Social Skills Questionnaire before and after SIS and the Subjective Feedback Questionnaire after SIS.

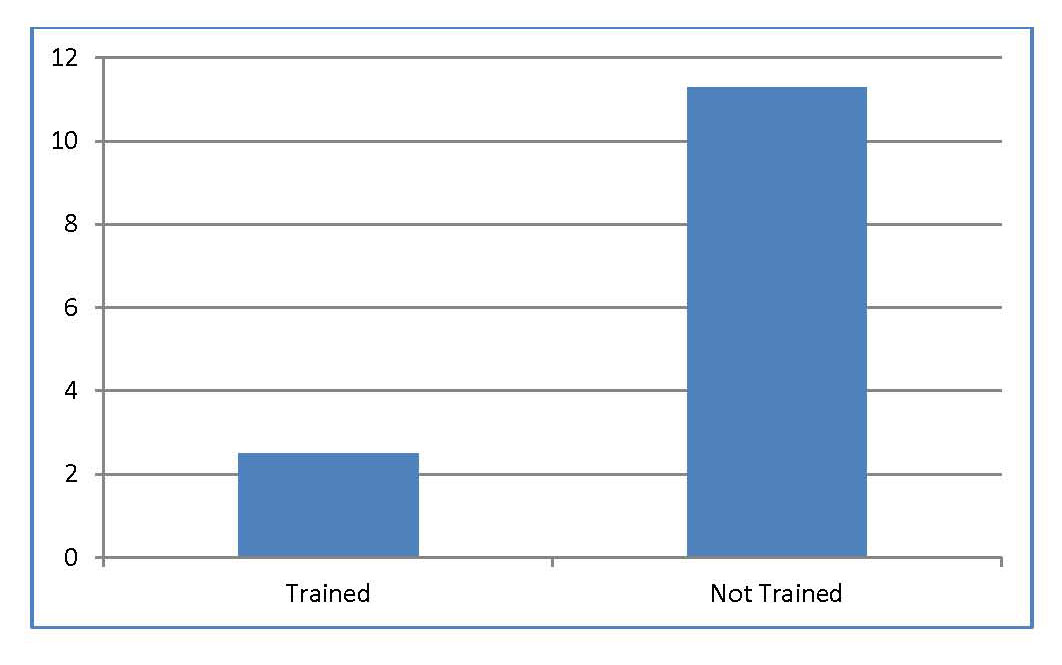

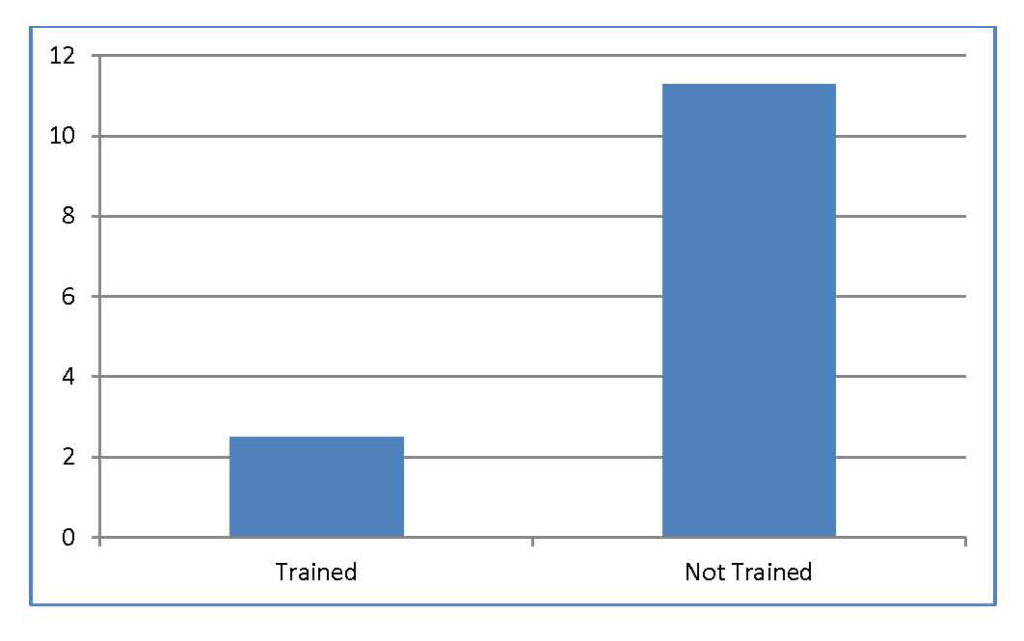

The Police Department monitored juvenile police offenses for all 9th-12th graders for a base-line period of 6 months before SIS and 19 months after SIS. During the pre-training period, the number of offenders among the 357 students who would later receive SIS did not differ statistically from the number of offenders among the 383 students who would not receive SIS. During 19 months after SIS, there were statistically significantly fewer juvenile police offenders (behaviors ranging from aggravated assaults, vandalism and burglaries, etc.) among 357 9th-12th graders who received SIS compared to the 594 students who did not receive SIS (this number includes the 211 9th graders who entered the school one year after the study began).

The graph below shows criminal juvenile police offenses for 595 untrained and 357 trained students who did not receive SIS per 100 students. The untrained students had about 450% more such offenses compared to the trained students and their offenses were more severe as ranked by the Police Department.

Juvenile Criminal Police Offenses per 100 students

The breakdown of criminal offenses among the 357 trained and 594 untrained 9th-12th graders during the 19 months of follow-up after training is shown in order of severity as ranked by the police department is in the following table. Traffic violations also appear in the table.

Criminal Offenses | Untrained | Trained | Traffic Violations | Untrained | Trained |

Robbery | 0 | 1 | Speeding | 11 | 12 |

Aggravated Assault | 3 | 1 | Ran Stop Sign | 3 | 1 |

Burglary | 16 | 1 | Failure to Yield | 1 | 1 |

Larceny | 1 | 0 | Reckless Driving | 1 | 2 |

Auto Theft | 1 | 0 | Careless Driving | 6 | 0 |

Other Assaults | 5 | 0 | Following too Close | 1 | 1 |

Arson | 1 | 0 | Other Hazard Violations | 7 | 2 |

Possession Stolen Property | 1 | 0 | Improper Equipment | 6 | 1 |

Vandalism | 7 | 1 | Non-Hazard Violations | 5 | 4 |

Narcotic Drug Law | 1 | 0 | Total | 41 | 24 |

D.U.I | 1 | 0 |

|

|

|

Liquor Law | 1 | 0 |

|

|

|

Drunkenness | 0 | 1 |

|

|

|

All Other Offenses | 12 | 2 |

|

|

|

Run-Away | 12 | 1 |

|

|

|

Overdose* | 5 | 1 |

|

|

|

Total | 67 | 9 |

|

|

|

As stated above, we were able to do a rigorous experimental design with 9th graders of two consecutive school years. A comparison was made between the trained 9th graders in the first year of the study and the untrained 9th graders in the following school year. During an equivalent 5-month pre-training period there were 5 juvenile police offenders among students who would later be trained, while there were no offenders among those who would not be trained. However, during an equivalent 7-month post-training period, there were 19 juvenile offenders among the 211 untrained students compared to 5 juvenile offenders among the 186 trained students. This difference is statistically significant (Chi Square = 5.877, df = 1, p = 0.015).

If we consider only criminal police offenses (omitting speeding and non-hazard violations), the untrained students have 8.5 times more criminal police offenses compared to the trained students. Scores on the SIS Social Skills Questionnaire showed highly statistically significant increases for 9th, 10th and 12th graders after SIS and were not significant for 11th graders after SIS. Students in all grades reported on the Subjective Feedback Questionnaire that they had learned and were motivated to use the skills learned.

DOWNLOAD COMMUNICATION SKILLS PROGRAM FOR PREVENTION OF RISKY BEHAVIORS

This study involves a large-scale replication done by 96 teachers, counselors, school nurses, school administrators, community volunteers and two project coordinators who were trained to facilitate SIS with students, parents and community in high risk environments. They trained 2,781 3rd -12th graders in classrooms, in student support groups, in a school within a chemical dependency treatment facility and in a school within a detention facility, as well as 227 parents and other adults. Two parent groups had Spanish speaking trainers and questionnaires were administered in Spanish. The SIS Social Skills Questionnaire was administered before and after SIS with students. Five additional questions pertaining to sexual behavior were added to the SIS Social Skills Questionnaire and were used by some of the trainers with 9th – 12th graders. The SIS Communications Questionnaire (measuring empowering and disempowering communications/behaviors), Quality of Life-Family Questionnaire (QLQ-F) and Quality of Life-Group Questionnaire (QLQ-G) measuring quality of life in the family and training group were administered to the adults before and after SIS. Both students and adults received the Subjective Feedback Questionnaire after SIS.

Although 2781 students were trained, data analysis is based on 2,695 students for whom paired pre and post-training questionnaires were available. Data loss occurred because of absences during pretest or posttest, lack of ID numbers to allow matching pre and posttests and two teachers who administered different pre and posttests making analysis impossible. All grades showed statistically significant increases on the SIS Social Skills Questionnaire, with 4th -12th grades showing highly significant results. Analysis by gender showed the same results. A higher score indicates a more positive empowering behavior.

Scores on the five added sexual behavior questions also showed highly statistically significant increases toward more empowering behavior, even when analysis was done by gender. Students in all grades reported on the Subjective Feedback Questionnaire that they had learned and were motivated to use the skills learned. Students in detention and treatment showed similar results to students in regular school settings. In addition, a group of 8 students in the treatment facility was evaluated by their counselors on the Communications Questionnaire before and after SIS. The counselors evaluated the students as being highly significantly more likely to use empowering communications/behaviors after SIS and engaging highly significantly less in disempowering communications/behaviors after SIS.

Adults reported highly statistically significant increases in empowering communications/behaviors and highly significant decreases in disempowering communications/behaviors as measured on the SIS Communications Questionnaire and highly significant increases on QLQ-F and QLQ-G after SIS. Adults reported on the Subjective Feedback Questionnaire that they had learned and were motivated to use the skills learned.

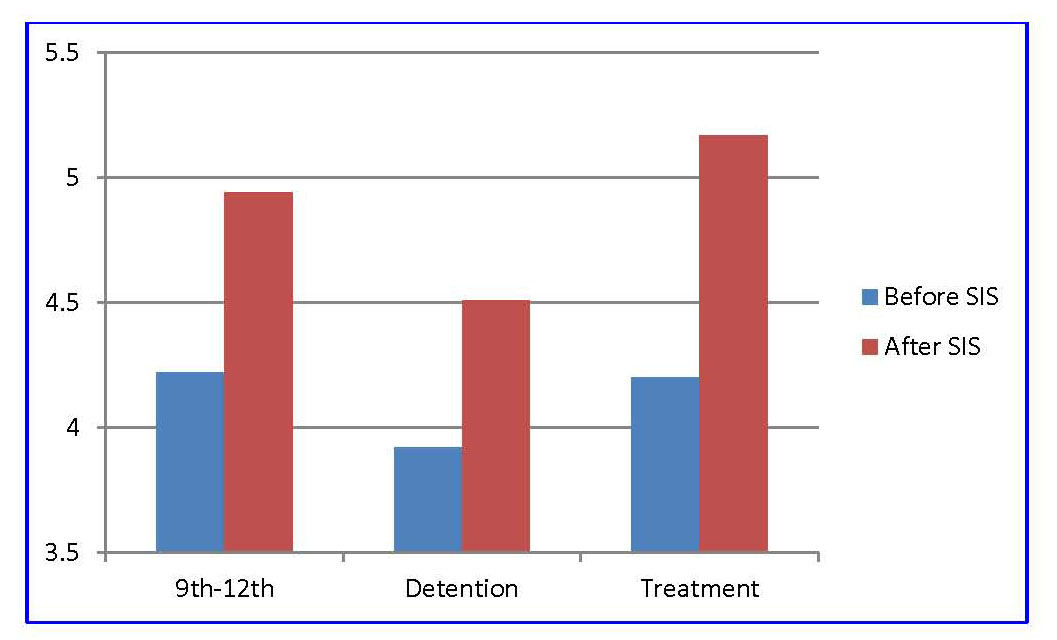

The next three graphs show highly statistically significant increases in willingness to implement constructive decisions in difficult situations among 3rd-12th graders after SIS training as measured on the SIS Social Skills Situation Survey which measures behavioral intentions to implement constructive decisions in difficult situations and the degree of comfort in doing so. These results were obtained by teachers, counselors, other school personnel and community volunteers.

Pre and post training means on the SIS Social Skills Situation Survey for 2,420 3rd-8th graders by grade (44 – 3rd, 148 – 4th, 426 – 5th, 446 – 6th, 245 – 7th and 1,111 – 8th graders) are presented below. Every grade moved significantly toward a greater willingness to make constructive decisions in difficult situations and felt more at ease doing so after training (higher scores after training), with p-values ranging from p < 0.048 for 3rd graders to p < 0.001 for 4th through 8th graders.

RESULTS FOR STUDENTS

Mean Pre and Post Training Scores on SIS Social Skill s Survey for 3rd-8th Graders (4-point scale)

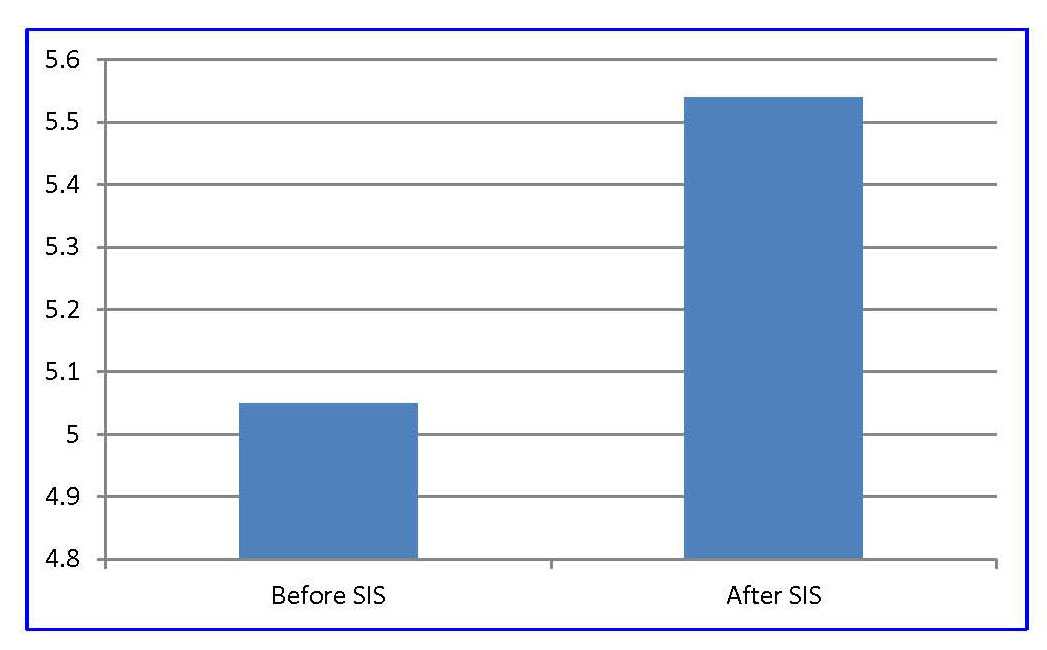

The following graph shows pooled data for 258 9th-12th graders. Results for 11 students in a detention school setting and 6 in a chemical dependency treatment school setting are also shown. Every group moved significantly toward a greater willingness to make constructive decisions in difficult situations and felt more at ease doing so after training, with p-values ranging from p < 0.040 for students in detention to p < 0.001 for 9th-12th graders in the regular schools.

Mean Pre and Post Training Scores on SIS Social Skills Survey for 9th-12th Grade Students in Regular Schools, in Detention and in Chemical Dependency Treatment (6-point scale)

Eighty-eight of the 258 9th-12th graders in regular schools received five additional questions on the SIS Social Skills Situation Survey pertaining to sexual behavior. As can be seen on the following graph, the shift toward a more thoughtful approach to sexual behavior was highly significant with p < 0.002. This shift was highly significant for both girls (p < 0.002) and boys (p < 0.004).

Mean Pre and Post Training Scores on Sexual Behavior Questions for 9th-12th Graders in Regular Schools (6-point scale)

RESULTS FOR YOUTH IN TREATMENT

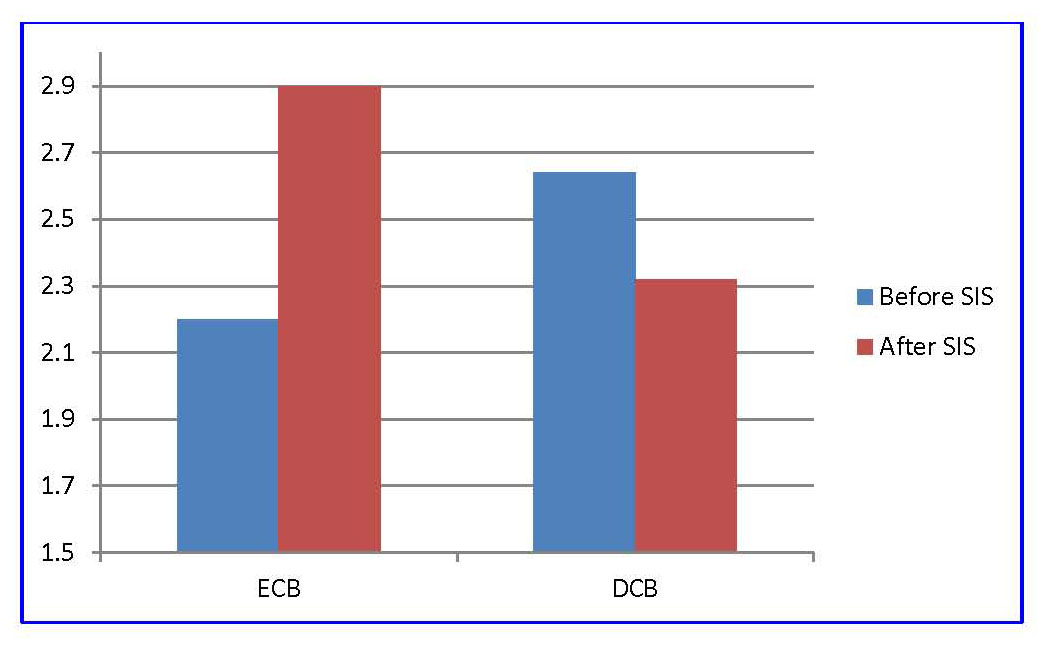

A group of 8 young people in treatment were observed before and after SIS training by their counselors who evaluated their communications/behaviors with the SIS Communications Questionnaire. As can be seen in the figure below, the ineffective communications/behaviors (composed of placating, blaming, being passive-aggressive, being irrelevant, being super-reasonable) decreased and straightforward communications/behaviors (SIS) increased after training. Both results were highly significant on a two-tailed t-test, with t = -5.80, df = 7, p < 0.001 and t = 3.81, df = 7, p < 0.007, respectively.

Mean Scores on Empowering (ECB) and Disempowering (DCB) Communications/Behaviors for Adolescents in Treatment as Observed by their Counselors Before and After SIS (4-point scale)

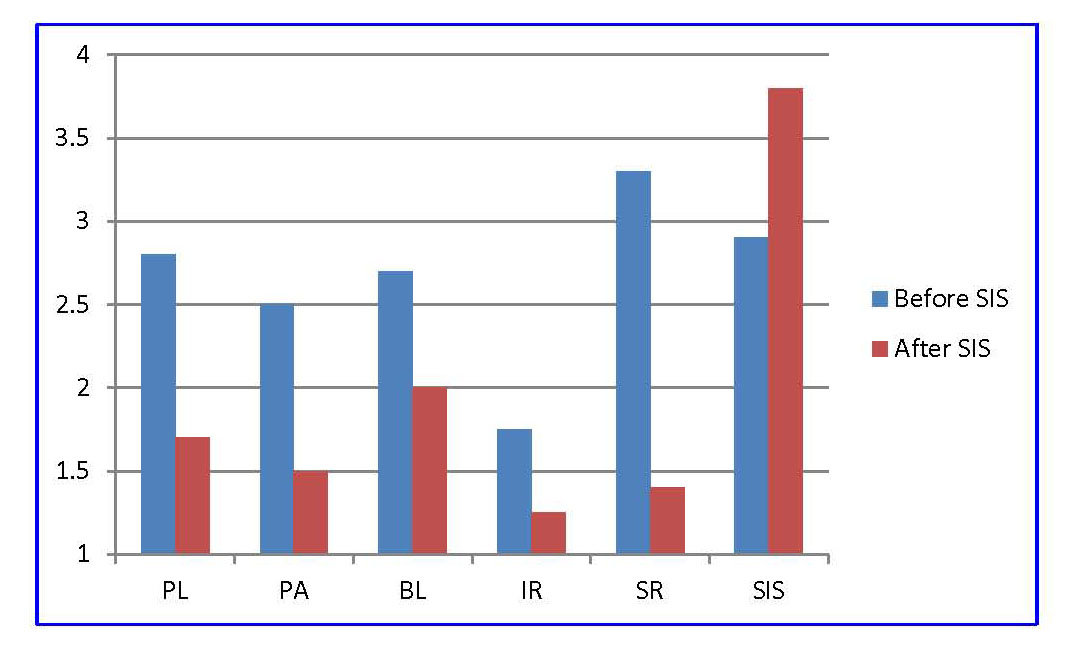

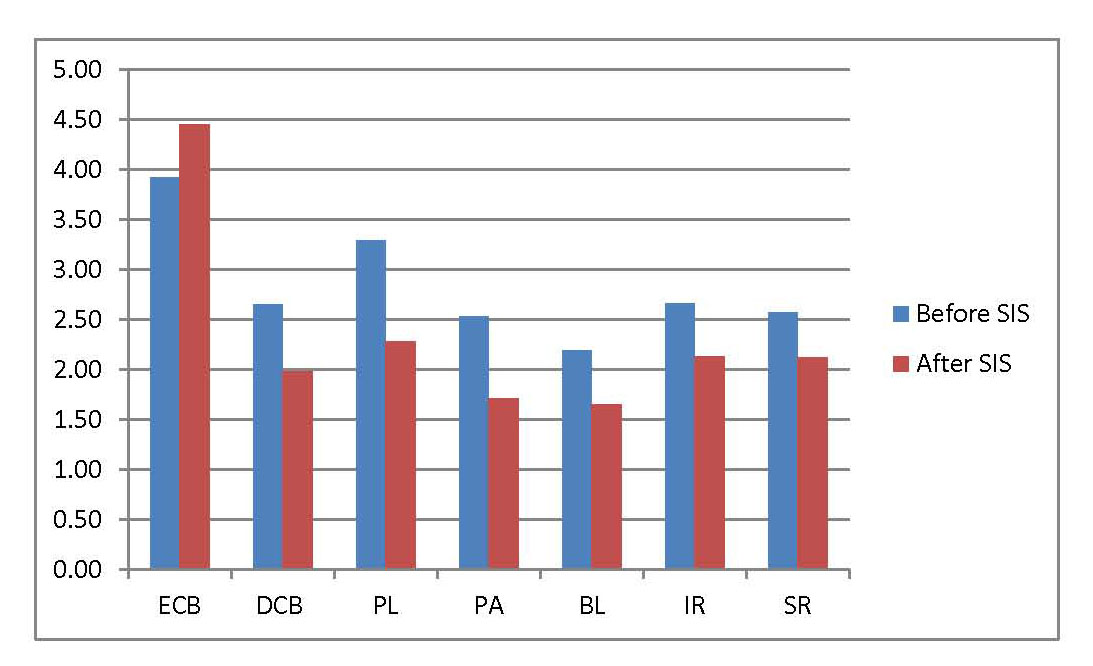

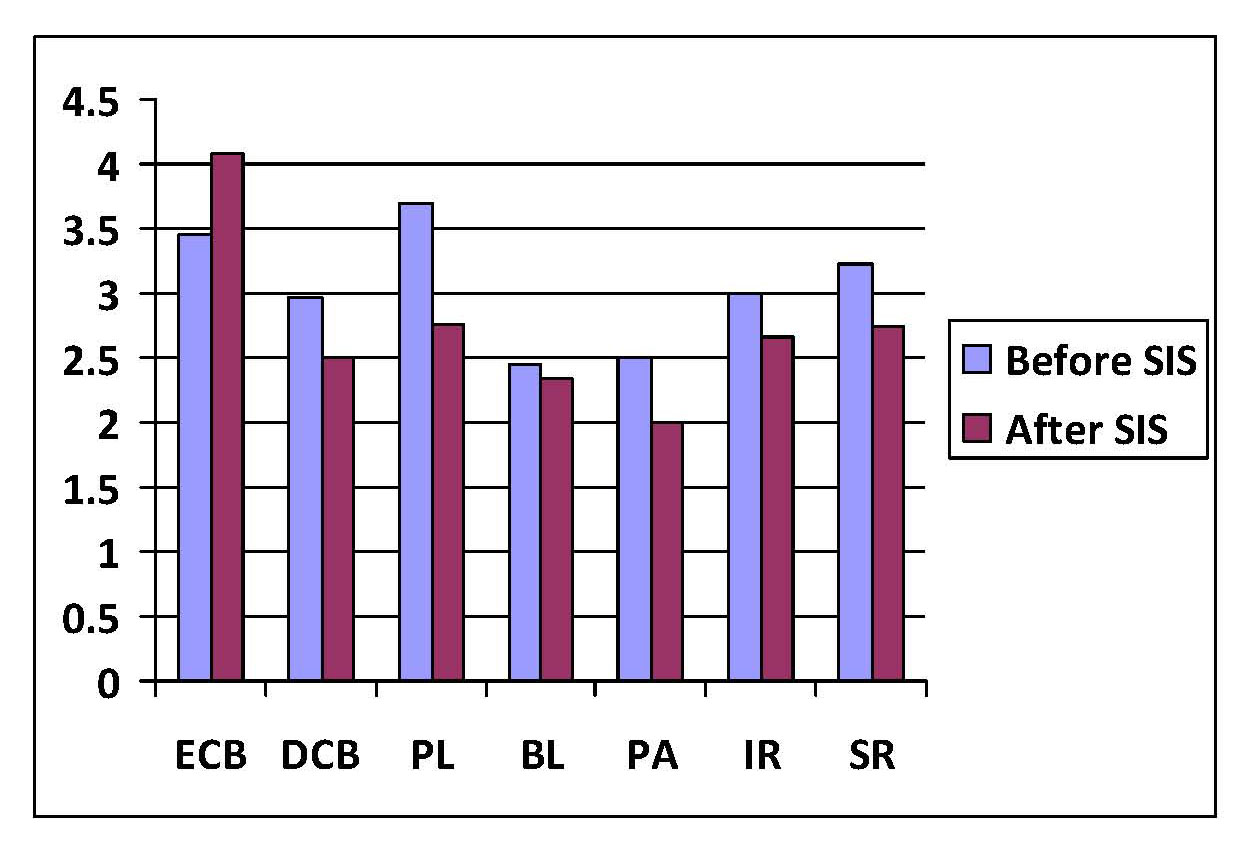

Another group of six adolescents responded to the SIS Communications Questionnaire before and after SIS training. The next graph shows pre and post training means on the SIS Communication Skills Questionnaire for these adolescents by factors of ineffective communications/behaviors, Placating (PL), Blaming (BL), Passive-Aggressive (PA), Irrelevant (IR), Super-Reasonable (SR) and effective communications/behaviors (SIS). The most desirable responses are low scores for ineffective communications/behaviors and high scores for effective communications/behaviors. As can be seen, all ineffective communications/behaviors are lower after training and the shifts are significant with p values from p < 0.033 to p < 0.001. The effective factor (straightforward communication) is higher after training and the shift is highly statistically significant with p < 0.001

Mean Pre and Post Training Scores on Placating, Passive-Aggressive, Blaming, Irrelevant, Super-Reasonable and Say It Straight Communication Factors for Adolescents in Treatment (6-point scale)

RESULTS FOR PARENTS AND OTHER ADULTS

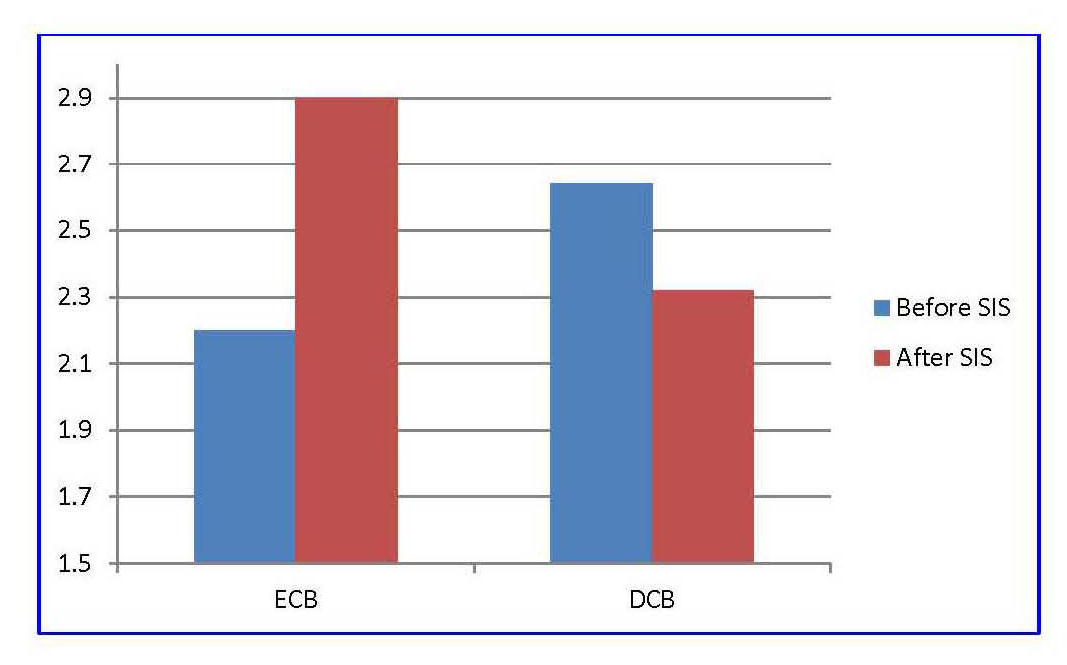

The next three graphs show results for parents and other adults who received SIS training in this study. The first graph shows results on the Communication/Behavior questionnaire for 100 participants on two categories, Empowering Communication/Behavior (ECB) and Disempowering Communication/Behavior (DCB). ECB includes saying it straight and positive support. DCB includes Placating, being Passive-Aggressive, Blaming/Bullying, being Irrelevant, and being Super-Reasonable. The last two graphs show results on the Quality of Life Questionnaire in the training group (165 participants) and the results on the Quality of Life Questionnaire in the family (117 participants).

Results on SIS Communication/Behavior Questionnaire for 100 Parents and Other Adults (6-point scale)

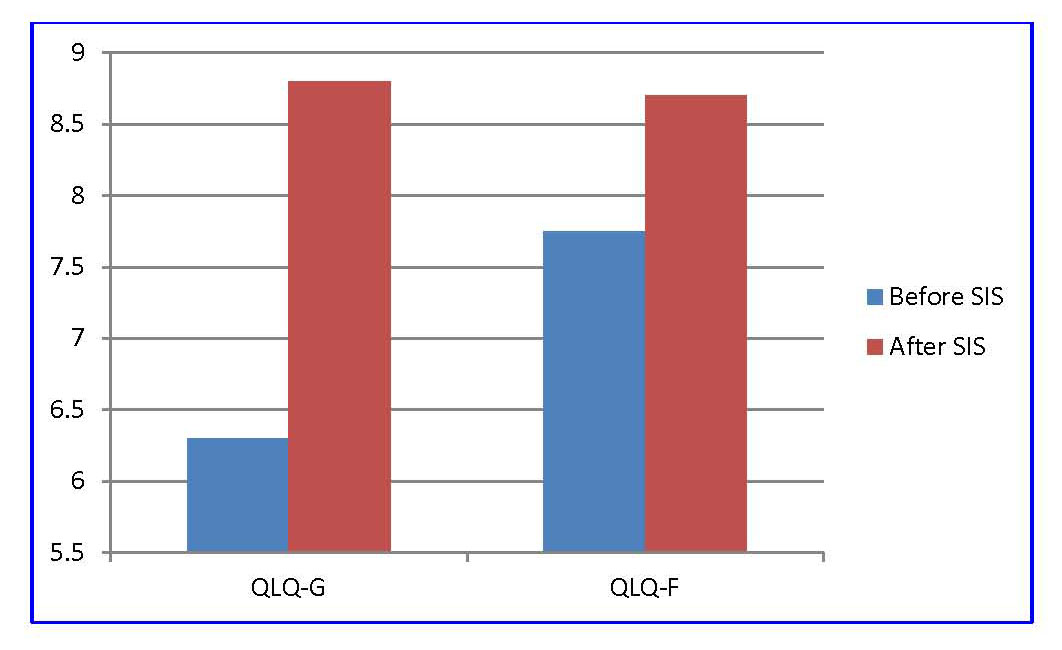

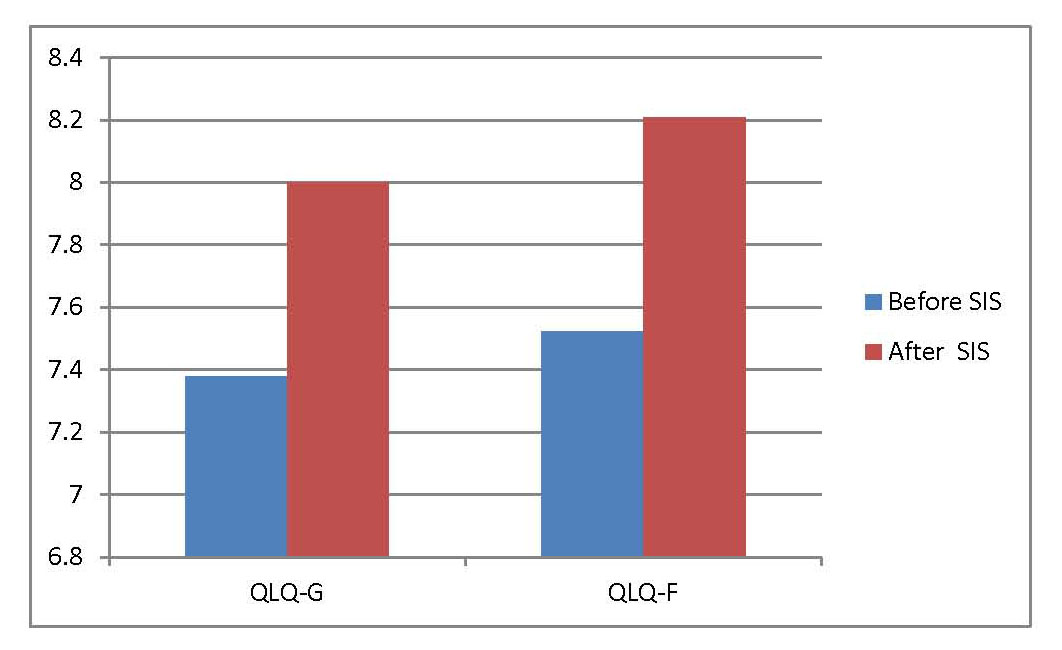

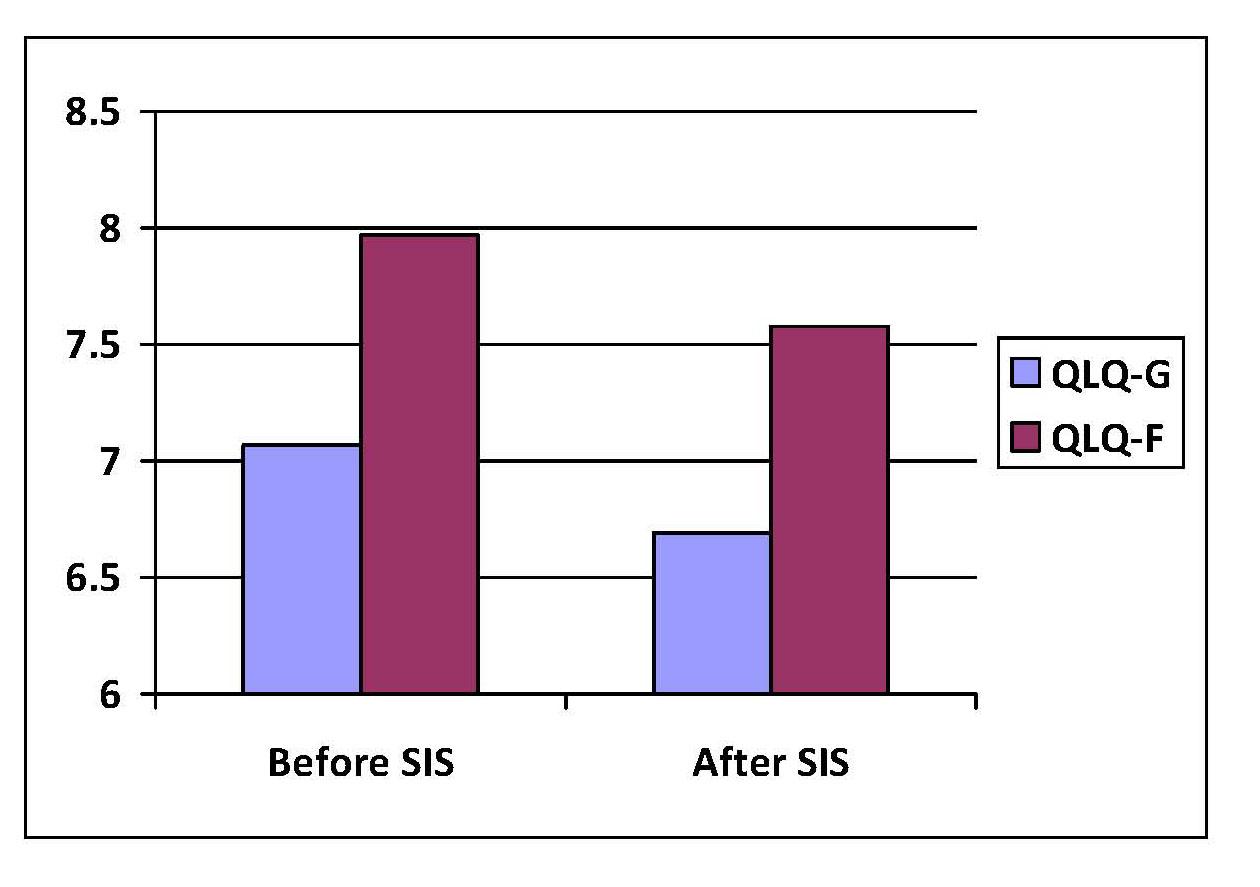

Results on SIS Quality of Life in their Training Group Questionnaire (QLQ-G) for 65 Parents and Other Adults and Quality of Life in the Family (QLQ-F) for 117 Parents and other Adults (10-point scale)

RESULTS FOR WOMEN IN RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT FOR CHEMICAL DEPENDENCY WITH THEIR CHILDREN AT THE SALVATION ARMY

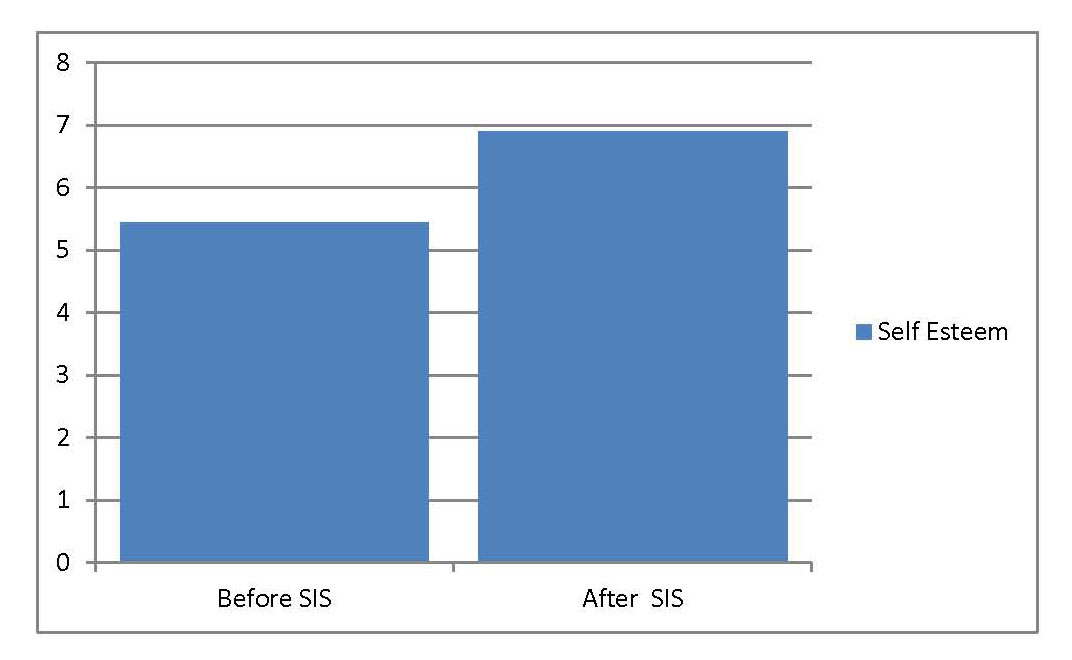

The effectiveness of Say It Straight communication training as a treatment component was evaluated with 36 mothers in residential chemical dependency treatment. All were indigent, 32 had previous criminal offenses and 14 were on probation or parole at the time of treatment. Self-reported disempowering behaviors (DCB) showed highly significant decreases after SIS training (p < 0.001) Empowering behaviors (ECB), quality of family and group life (QLQ-F and QLQ-G) showed significant increases (p = 0.001, 0.008, p = 0.015 respectively). Self-esteem (SE), assessed with one group of eight mothers, showed a highly significant increase after training (p = 0.009). Statistically significant differences between mothers in treatment an average of 40 days compared to those in treatment 141 days prior to training disappeared after 10-16 hours of training, although the latter group also showed positive changes. Reports regarding training effectiveness were very positive. Results indicate this training is an important addition to treatment and may have implication for shortened treatment time, increased treatment retention and reduction in relapse/recidivism.

Empowering behaviors (ECB) show highly significant increases after training, the composite of disempowering behaviors (DCB) and all the individual disempowering components, placating (PL), passive-aggressive (PA), Blaming (BL), irrelevant (IR) and super-reasonable (SR) show highly significant decreases (p values ranging from p = 0.000 to p = 0.001) after training.

Results on SIS Communication/Behavior Questionnaire (6-point scale)

The average pre and post training scores for 34 mothers on the Quality of Life Questionnaire both in the peer group and family are shown below. The results show a statistically significant increase for the peer group and a statistically highly significant increase in the family.

Results on Quality of Life Questionnaire (10-point scale)

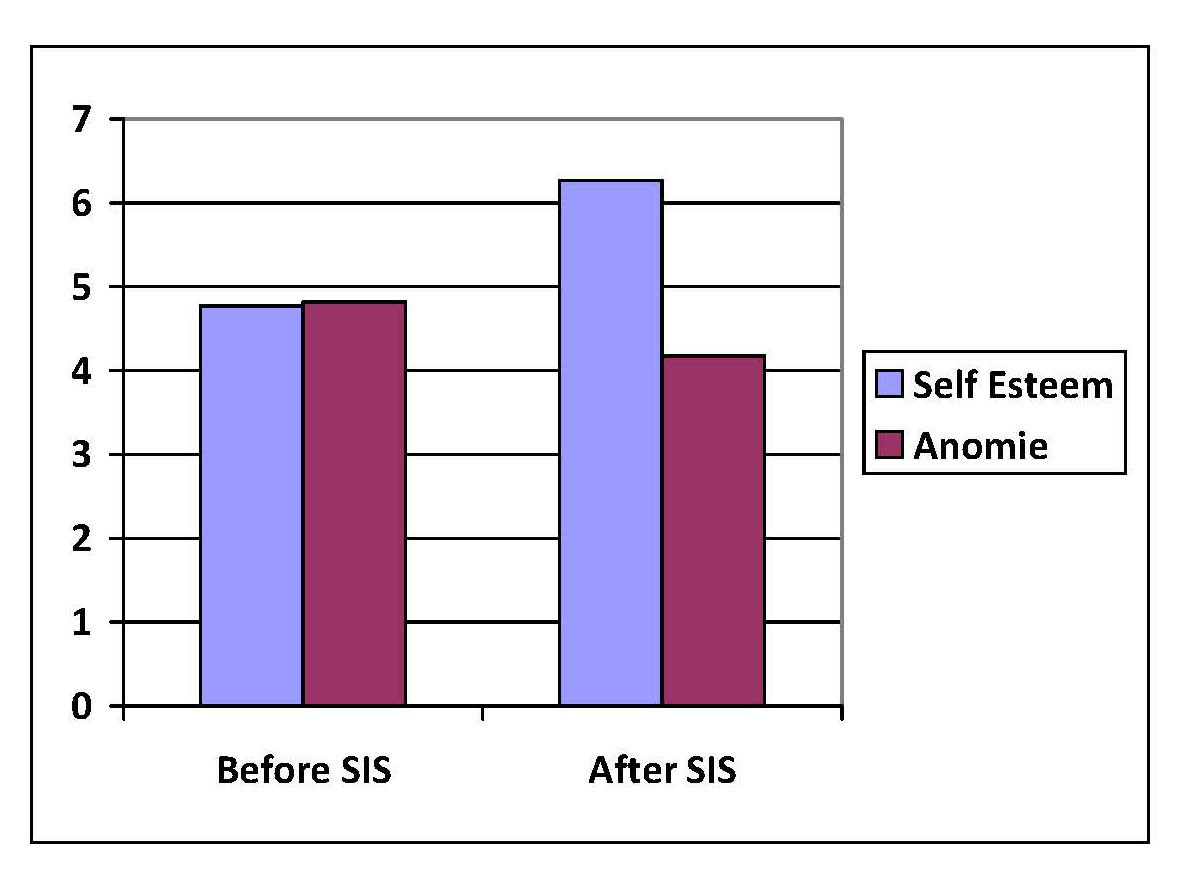

The training scores for 8 mothers on self esteem are shown below. The results show highly statistically significant increases in self-esteem.

Results on the Self-Esteem Questionnaire (9-point scale)

RESULTS FOR MEN AND WOMEN IN RESIDENTIAL TREATMENT FOR ADDICTIVE DISORDERS, (ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUGS, SEXUAL ADDICTION, EATING DISORDERS , COMPULSIVE SHOPPING AND GAMBLING) AND CONCOMITANT PSYCHIATRIC DIAGNOSES

This study evaluated SIS in a residential treatment facility (chemical dependency, sexual compulsivity, compulsive gambling, eating disorders and psychiatric diagnoses) with 26 men and women. Effectiveness of SIS was measured by comparing leaves from the treatment facility against medical advice before SIS and during SIS, as well as with questionnaires used in Study 5. Another questionnaire was used to evaluate anomie (the sense of alienation) before and after SIS. Self-reports of empowering behaviors, quality of family and group life and self-esteem showed highly significant increases following SIS. Self-reports of disempowering behaviors showed highly significant decreases following SIS and anomie (a person’s perceived level of alienation from self and from others) showed a significant decrease. Subjective reports regarding training effectiveness were also very positive. One resident reported, “finding his voice” as a result of SIS and how this was important for him in coping with triggers for relapse. Treatment staff reported that SIS resulted in a prevalent attitude of increased concern among residents for one another’s recovery and willingness on the part of residents to go out of their way to assist staff in forestalling residents leaving against medical advice as well as intervene informally on their own with greater frequency. Leaves against medical advice were significantly reduced (odds ratio of 2.1). This is a large effect size showing that SIS leads to an increase in treatment retention and completion.

Average pre and post training scores for 26 residents in empowering behaviors (ECB), the composite of all disempowering behaviors (DCB) and the separate components of disempowering behaviors, people pleasing (PL), blaming or bullying (BL), back-stabbing (PA), being disruptive or out of it (IR) and lecturing (SR) are shown below. The results show highly statistically significant increases in empowering communications/behaviors and highly significant decreases in disempowering communications/behaviors.

Results on SIS Communication/Behavior Questionnaire (6-point scale)

Average pre and post training scores for 26 residents on the Quality of Life Questionnaire both in the training group (QLQ-G) and family (QLQ-F) are shown below. The results show highly statistically significant increases on both measures.

Results on Quality of Life Questionnaire (10-point scale)

Average pre and post training scores for 26 residents on self-esteem and anomie are shown below. The results show highly statistically significant increases in self-esteem and significant decreases in anomie.

Results on the Self Esteem and Anomie Questionnaire (9-point scale)

References

Englander-Golden, P. SAY IT STRAIGHT: Training in Straightforward Communication. (1983a). Workbook for Students (Younger). Denton, TX: Golden Communication Books, Say It Straight Foundation. Translated into Cantonese Chinese, 1985. Also translated into Spanish, 1993.

Englander-Golden, P. SAY IT STRAIGHT: Training in Straightforward Communication. (1983b). Workbook for Students (Older). Denton, TX: Golden Communication Books, Say It Straight Foundation. Translated into Cantonese Chinese, 1985. Also translated into Spanish, 1993. Englander-Golden, P. (1983, subsequent editions 1990, 1991). SAY IT STRAIGHT – Training in Straightforward Communication. Manual for Trainers. Denton, TX: Golden Communication Books, Say It Straight Foundation.

Englander-Golden, P. (1984) Say It Straight Training: Substance Abuse Prevention. A one-hour and a 30-minute videotape.

Englander-Golden, P., Elconin, J. and Miller, K.J. (1985). SAY IT STRAIGHT: Adolescent substance abuse prevention training. Academic Psychology Bulletin, 7 , 1, 65-79.

Englander-Golden, P., Elconin, J. and Satir, V. (1986). Assertive/leveling communication and empathy in adolescent drug abuse prevention. Journal of Primary Prevention, 6, 4, 231-243.

Englander-Golden, P., Elconin, J., Miller, K.J. and Schwarzkopf A.B. (1986). Brief SAY IT STRAIGHT training and follow-up in adolescent substance abuse prevention training . Journal of Primary Prevention, 6, 4, 219-230.

Benard, B. (1988). Peer programs: The loadstone to prevention. Prevention Forum, 2,8,6-12.

Englander-Golden, P., Jackson J.E., Crane K., Schwarzkopf A.B. and Lyle P. (1989) “Communication Skills and Self-Esteem in Prevention of Destructive Behaviors.”Adolescence, 24, 94, 481-502.

Morton, D. (1990). Personal communication to the SIS Foundation. Mr. Morton is a high school counselor who interviewed students to see if observed changes in sexual behavior were due to fear of STD or as a result of SIS.

Englander-Golden, P. and Satir, V. (1991). SAY IT STRAIGHT: From Compulsions to Choices. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

Englander-Golden, P. (1993). Say It Straight Training: In the Classroom. One-hour videotape developed on grant from U.S. Department of Education #S241A30052. (Available from Say It Straight Foundation, P.O. Box 50752, Denton, TX 76206.)

Englander-Golden, P. (1993). Say It Straight Training: Student Support Group. One-hour videotape developed on grant from U.S. Department of Education #S241A30052. (Available from Say It Straight Foundation, P.O. Box 50752, Denton, TX 76206.).

Englander-Golden, P. (1993). Say It Straight Training: Family-Community Series. One-hour videotape developed on grant from U.S. Department of Education #S207A21054. (Available from Say It Straight Foundation, P.O. Box 50752, Denton, TX 76206.)

Englander-Golden, P. and Golden, D.E. (1993). SAY IT STRAIGHT: Training in Straightforward Communication. Trainer Manual for Parent and Community Training. Denton, TX: Golden Communication Books, Say It Straight Foundation. Also translated into Spanish.

Englander-Golden, P. and Golden, D.E. (1993). Say It Straight: Training in Straightforward Communication, Workbook for Parents and Community Members. Denton, TX: Golden Communications Books, Say It Straight Foundation. Also translated into Spanish.

Englander-Golden, P. and Golden, D. E. (1996) The Impact of Virginia Satir on Prevention of Destructive Behaviors and Promotion of Wellness. Journal of Couples Therapy, 3-4, 6,69-93. Co-published simultaneously in B.J. Brothers, ed. Couples and the Tao of Congruence, The Haworth Press, Inc.

Englander-Golden, P., Snow, C.P., Haag, M.S., Golden, D.E., Brookshire, W. & Chang, T. (1996) Communication skills program for prevention of risky behaviors with students and families. Journal of Substance Misuse for Nursing, Health and Social Care. 1, 38-46.

Englander-Golden, P. and Golden, D.E. (1997). Say It Straight: Training in Straightforward Communication, Workbook for College Students. Denton, TX: Golden Communications Books, Say It Straight Foundation.

Englander-Golden, P., Gitchel, E. & Golden, D.E. (1998). SAY IT STRAIGHT training with mothers in chemical dependency treatment.” Presented at the 42nd ICAA International Institute on the Prevention and Treatment of Dependencies. Malta. August 30 – September 4. Published in Conference Abstracts.

Hardy, R.B. & Englander-Golden, P. (1998) Effectiveness of Say It Straight Training in Out-Patient Chemical Dependency Treatment. Presented at the 42nd ICAA International Institute on the Prevention and Treatment of Dependencies. Malta. August 30 – September 4. Published in Conference Abstracts

Englander-Golden, P., Gitchel, E., Henderson, C.E., Golden, D.E. & Hardy, R. (2002) “Say It Straight” Training with Mothers in Chemical Dependency Treatment, Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 35(1). 1-22.

Wood, T.E., Englander-Golden, P., Golden, D.E. & Pillai, V.K. (2010) Improving addictions treatment outcomes by empowering self and others. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 10 (5) 363-368.

Haag, M., Wood, T. and Holloway, L. (2011) Impacting quality of life at a homeless shelter: Measuring the effectiveness of Say It Straight. International Journal of Intersisciplinary Social Sciences. (5) 12, 195-203.

Golden, D.E. and Englander-Golden, P. (2014) Say It Straight: From breakdowns to breakthroughs, Virginia Satir International Journal, (2) 1, 9-27.